OUR HISTORY

Epson embarked on its journey as a watch parts manufacturer on the shores of Lake Suwa in Japan in 1942. Over the past 80 years the company has evolved to be a world-leader in innovation and technology.

Epson emerged from nature’s magnificence along the shores of Lake Suwa.

Our connection to this ecosystem drives our business. Technologies that propel the development of innovative new products must contribute to a thriving environment. Epson’s unique, efficient, compact, and precision technologies represent this philosophy. It’s in our DNA. Our history of creativity and challenges originated from assembling watch components, leading to the development of technologies responsible for many world-first products.

From printers and projectors to robots and wearables, our technologies improve life worldwide. In 2022, we at Epson celebrate our 80th anniversary. We promise to continue to serve society and our planet, creating a sustainable future that enriches people’s lives everywhere.

CEO Message

Moving forward under our new corporate purpose.

"Our philosophy of efficient, compact, and precise innovation enriches lives and helps create a better world."

We at Epson have always exercised creativity and challenged ourselves to deliver products and services that exceed the expectations of our customers by drawing on the efficient, compact, and precise technologies we have developed since the company was founded.

The world is facing some serious issues, climate change and rising prices among them. As people have sought to enrich their lives, the focus was placed on material and economic wealth, and the drive to enrich only ourselves may have caused many of the societal issues we face today. Moving forward, therefore, I believe we should seek to enrich the entire planet, and not just ourselves. Rather than only material and economic enrichment, we should also seek spiritual and cultural enrichment.

The pursuit of ever greater efficiency, compactness, and precision that we have embraced for so long goes well beyond technology. "Efficient, compact, and precise" encompass a philosophy for eliminating waste, reducing dimensions, and increasing precision. I believe that this approach can enable us to create even greater social value. In other words, it is the idea that less is more. We will continue to adhere to Epson's unique philosophy of efficient, compact, and precise innovation, take advantage of the tremendous value that those innovations yield to overcome global environmental problems and other societal issues, and work together to enrich people's lives and make a better world.

With this in mind, we established a corporate purpose statement that reads, "Our philosophy of efficient, compact, and precise innovation enriches lives and helps create a better world." Epson's goal is to collaborate with our customers and partners to achieve sustainability and enrich our communities.

Yasunori Ogawa

President and CEO

Seiko Epson Corporation

April 2024

History milestones

Our Journey

Chapter 1 - The beginning: The shores of Lake Suwa, Nagano Prefecture.

Products Made in Harmony with Nature

Suwa, where it began. Lessons from Nature.

Everyone has their hometown. We do, too. Suwa in the heart of Japan. Our story began in an old miso warehouse from the vision of Hisao Yamazaki and his nine employees. We grew up here surrounded by Lake Suwa and the highlands of the Yatsugatake Mountains. To this day, we are inspired by this land.

Suwa has taught us much. A way to live in harmony with nature, which we’ve passed down for generations. The inhabitants have lived and thrived in this harsh environment observing the cracks of the Omiwatari pressure ridge on Lake Suwa’s icy surface. Here, the winter cold penetrates everything, a harshness our ancestors understood. But, instead of leaving, they lived on the land, celebrating the Earth, Nature, and Suwa, and living in harmony with the lake and the mountains.

This way of life was natural back then, and natural for us today. This is the spirit of our craftsmanship and the inspiration for our quality.

Eight decades ago, Epson embarked on its journey, assembling watch components.

Nagano Prefecture in Japan boasts lush flora, the majestic peaks of the Japan Alps, and diverse wildlife. Here Daiwa Kogyo — the forerunner of Epson — launched its business on May 18, 1942, from the shores of Nagano’s largest lake, Lake Suwa.

The inhabitants of the area have long revered the lake’s natural surroundings, living in villages and on mountains with gratitude for the bounty the land provided. Lake Suwa encapsulates nature’s beauty and severity — and the sanctity of the environment. An environment that has long sustained the people of Suwa. Over 2,000 years ago in the Jomon period, residents fished Suwa’s waters and quarried its ice to transport across the lake. For many years, Lake Suwa was central to daily survival.

Cold, harsh winters impeded agriculture, so Suwa’s residents relied on hunting and mountain foods for sustenance, learning to live with the land. A close relationship that still exists today. The Suwa residents were pioneers who respected the environment.

Today, Epson employs around 77,000 people worldwide, and global corporate sales exceed one-trillion yen. However, it embarked on its journey from an old, converted miso warehouse, assembling watch parts.

The clean water and fresh air created the perfect environment to produce precision instruments.

But the region was never wealthy, and Hisao Yamazaki, the company’s founder, saw potential in the place where the raw silk industry once flourished. He envisioned a new industry that would restore vitality to the area and the lives of locals. Yamazaki returned to Suwa to take over the family business.

Together with Suwa’s Mayor and other prominent business leaders, Yamazaki approached Shoji Hattori, the managing director of Daini Seikosha (now Seiko Instruments) with the prospect of developing more precision instruments.

The group believed that Suwa’s climate was like Switzerland’s with low summer humidity, so it would be a perfect environment for a precision industry. They believed Suwa could be the Switzerland of the East and began clock assembly operations. The company had only nine employees.

Hisao Yamazaki’s vision is still alive today.

Yamazaki’s passion for establishing a Japanese watch industry led him to collect parts in the late 1940s. If he didn’t have certain parts, he made them. By January 21, 1946, he had the parts to assemble four timepieces, which were completed the next day after a night of assembly.

Only two of the four watches worked, but this would pave the road with an ethos of experimentation that lives on at Epson today.

Yamazaki showed strong resolve by proclaiming, “I’m going to pour my heart and soul into this. We’ve got to all come together to ensure this business takes root here.”

This emotional greeting still inspires Epson today. Later Shoji Hattori, who since became chairperson, would describe Yamazaki as a man of integrity and effort. Yamazaki’s attitude still permeates Epson’s corporate culture.

Chapter 2 - Manufacturing in harmony with nature.

At Seiko Epson, we dedicate ourselves to contributing to the environment while manufacturing our products.

It’s the promise we made to Suwa.

We were born from a land surrounded by nature's magnificence, with a lake spreading out before us. Even those of us who knew only this place easily understood the beauty of the environment. The company founder, Hisao Yamazaki, pledged never to pollute Lake Suwa, but to preserve its beauty. Nature, despite its majesty, is delicate and vulnerable and regardless of how masterfully we create, our value diminishes if we destroy nature.

We were born in harmony with our community and nature. Lake Suwa emerged from tectonic activity millions of years ago. Naturally, Suwa has its past and present. Yamazaki made his promise to Lake Suwa in exchange for the ability to manufacture in the area. As a result, his vision has survived generations and produced our values. Without nature, our business would not be possible.

When we look around, we see stately trees reaching high into the sky. Listen carefully, and life is all around. Even today, Lake Suwa is brilliant. Nature's bounty in the right place and the right time. Our craftsmanship has reached every corner of the world, and we continue to create while tackling the toughest global issues.

From the time we were founded, our mission has been to contribute to our environment, manufacturing in harmony with nature.

“We must never pollute Lake Suwa.” These are the words of our founder, Hisao Yamazaki. To develop our business on these shores nestled in nature, we developed a harmonious relationship with the local community and worked to preserve the environment — this was our mission from the beginning.

We clean our wastewater to preserve Lake Suwa, and in the 1970s, we set in-house, voluntary environmental standards that were stricter than the legal and regulatory limits to prevent pollution.

As a manufacturer, creating and delivering new products often negatively affects the environment. However, balancing environmental preservation with operations has always been the heart of our business at Seiko Epson. It’s a culture passed down from generations that has remained intact as our global business developed and expanded.

Technology and information have little value without humanity and creativity.

In the 1980s, as awareness of risks to the ozone layer became an issue, Seiko Epson became the first company in the world to pledge to go CFC-free. Tsuneya Nakamura, a former CEO, said, “We cannot use something that we know is hurting the environment. Technology and information have no value in themselves but only become useful and valuable through humanity and creativity in the hands of people who use them.” In 1992, the company achieved a complete elimination of specified CFCs in Japan, and the following year we achieved this worldwide.

Nakamura said, “In the absence of an effective alternative, our CFC-free activities, proceeded without clear prospects for success, and challenged what's possible. We received the US Environmental Protection Agency’s Stratospheric Ozone Protection Award, which I accepted in Washington on behalf of all our employees. This was a memorable experience.”

Eighty years after our establishment, our beliefs and values remain unwavering. In 2016, we launched the PaperLab A-8000, an office papermaking system that destroys confidential paper documents and recycles the paper in a dry process, thus conserving a precious resource, water.

We have included sustainability in our long-term vision statement. Our Environmental Vision 2050 states that we will become carbon negative and underground resource free — a lofty goal that we intend to accomplish.

Which social issues can we solve through our technology?

As a small company, born from an area rich with nature, that has grown through coexisting with its local community, we continue to work towards solving social issues today.

The ideas that have guided our company since its inception remain steadfast within our current management philosophy, which we express as “The Earth is Our Friend.”

Chapter 3 - Comprehensive watchmaking. The challenge to become the best demands accuracy. The answer to this challenge was efficient, compact, and precision technologies.

We provided the world with accurate time.

It was 1959 when our most important project began. Project 59A would redefine horology, from mechanical watches to new technologies. The goal: create the next generation of highly accurate watches to change sporting competitions. This would lead to the world’s first quartz watch and also to our compact, efficient, and precision technologies. A mindset that we still maintain today.

It all started with a dream to change the world. We competed in the international watch competition held in Switzerland, the pinnacle of mechanical watchmaking. Our first attempt in the wristwatch division was a failure, but it drove us to go forward. Later, thanks to the tireless effort of employees, we achieved more accurate timepieces and garnered some of the world’s top awards.

For us though, it’s not about awards. It’s about delivering accurate time to people around the world. So, we made our quartz technology, the fruit of our quest for compact, efficient, and precision technologies, available to the world. Now this patented technology spans the globe and gives everyone more accurate time. We believe time belongs to no one; we all have a right to it. Many years have passed since then, but our quest for compact, efficient, and precise technology continues.

The thinking behind efficient, compact, and precision technologies.

Our company’s mindset has always been to create and manufacture products with technology that saves energy, time, effort, and space.

Watches in the mid-20th century required more power, were larger, and less accurate than the watches of today. The goal was to make them smaller, more accurate, and more efficient.

As a result, Seiko watches deliver convenience and make life more colourful. Epson employees strive to master efficient, compact, and precision technologies, bringing these qualities to products and the world.

After 1945, Daiwa Kogyo and the Suwa Plant of Daini Seikosha — which merged into Suwa Seikosha in 1959 — began full-scale production of wristwatches. In 1959, thanks to some excellent engineers, the company developed Japan’s first originally designed wristwatch, the Marvel. The Japanese considered it an amazing feat for its accuracy and quality, and the Marvel dominated the first five places in Japan’s Ministry of International Trade and Industry’s Quality Comparison Testing Board for the Assessment of Domestic Timepieces.

By 1958, the company dominated the first nine places in the Quality Comparison Testing Board for the Assessment of International Timepieces. However, never content with the status quo, Seiko Epson sought to become the global leader.

Project 59A and the birth of the world’s first quartz wristwatch.

This event marked the beginning of efficient, compact, and precision technologies. Project 59A (its internal designation) would become the watch to change watchmaking.

The name refers to the year 1959, and “A” marks the project’s importance. It kicked off with three proposals: an electronic tuning fork watch, an area where another company already had the lead, a watch with an electric balance wheel, and a quartz timer, which was about the size of a locker at the time.

The first two proposals had critical weaknesses, so efforts went into the quartz timer, which would alter the course of horology. The first quartz timepieces we developed were still the size of table clocks, but the company began entering timepieces in the Neuchâtel Chronometer Competition in Switzerland, which determines the benchmark for timepieces. While repeatedly striving to reduce size and improve accuracy, the company began taking awards for the marine chronometer and board categories, showing the world a new level of standards. While refining technology through the Observatory Chronometer Competition, the company further reduced size and power efficiency through practical applications such as the Antarctic observation team and the Shinkansen bullet train. By 1969, ten years after the 59A project, Seiko introduced the world’s first quartz wristwatch, the Seiko Quartz Astron 35SQ.

Manufacturing automation and expansion, leading to mass-production on a global scale.

Turning attention to manufacturing for a moment, Seiko Epson streamlined design, division of labour (Belt-Line), and automated assembly in the mid-1960s, as high precision requires high coordination. The origin of our current manufacturing solutions — or robotics — is an automated technology. In 1983, the company began external sales of precision assembly robots, and by 2009, work had expanded. Later came the Compact 6-Axis Robots, offering optimal performance for precision assembly of small parts.

As automation evolved in watchmaking, Seiko Epson became a global leader in wristwatch production.

Technology exists to serve everyone, not a select few

The company not only continued to develop quartz watch technology but also pursued the advances in accuracy in mechanical watches, rivaling some big names in the Neuchâtel Chronometer Competition. In 1964, Seiko entered its first mechanical watch, placing poorly at 144th.

However, that poor result inspired improvement, and in 1968 at the Geneva Observatory Chronometer Competition, Seiko dominated the top places in the mechanical wristwatch category. This effort verified our precision technology. Among the winners was Kyoko Nakayama, the first woman to hold the title of Contemporary Master Craftsperson and the first woman in the competition’s long history to enter and win the regulateur’s prize.

High-precision competitions are like F1 races and are distinct from commercial products. To make better products available to more people, the technology and skills used to develop watches came to life in the Grand Seiko brand.

We didn’t reserve its technology to develop compact, efficient, and accurate watches for a select few. Instead, we made the technology available so that everyone could enjoy world-quality, accurate watches. The result was quartz wristwatches, a technology developed in Japan, spread around the world, putting accurate time on the wrists of the global population.

Today, Seiko Epson remains steadfast in the belief that technology alone doesn’t solve problems; the mindset of employees does.

Compact, efficient, and precision technologies reduce environmental impacts, and this corporate stance has broadened to provide confidence and hope to not only employees but also to communities around the world.

Chapter 4 - If it doesn’t exist, we make it.

It is this atmosphere of creativity and challenge, which gives rise to many world’s firsts.

If it doesn’t exist, we’ll make it. Japan was in a frenzy. We had marked the time of victory.

The prestigious international sporting event of 1964 filled the country with excitement. Athletes from around the world had trained and devoted their lives to this day. Hours, minutes, and seconds determine wins and losses. We are the keepers of time. And we let the world know with the slogan, “One step further than previous timekeeping devices.”

The world celebrated this new accuracy and speed, which marked a new era in timekeeping for the Games. And this success would lead to printing innovations that would change the world, including the first compact, lightweight digital printer and the quartz watch.

We developed and manufactured compact, efficient, and precision technologies required to produce quartz watch components unlike any the world had ever seen. Creating something from scratch is never easy.

One from zero. Two from one. The distance is the same, but the difference is vast. Some say that Suwa and the land around the lake emerged from land reclamation in the Edo period. Humanity also made this land. We create what has yet to be created. This spirit is the driving force behind manufacturing at Epson.

From watches to printers: The little-known history of Seiko Epson.

Now in 2022, many know Seiko Epson — or just Epson — for its printers and projectors.

Seiko Epson has its roots in watchmaking, but not many people know what led to Epson’s business expansion. The international sporting event in 1964 where Seiko became the official timekeeper was a watershed moment for the company.

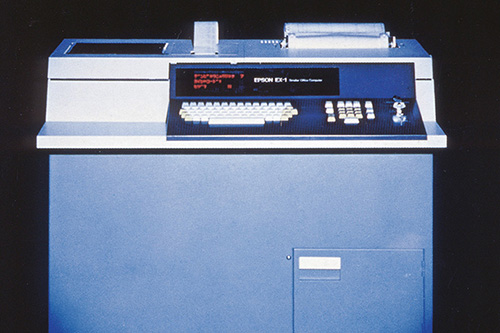

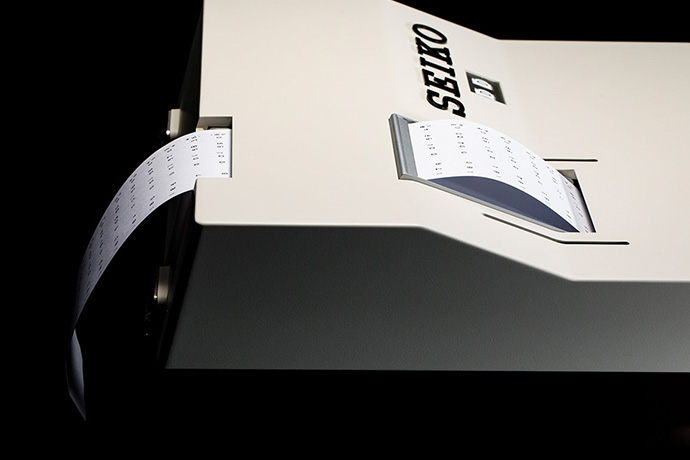

Measuring and recording race results quickly and accurately

Science was the theme of this event, and Seiko, with the slogan, “A step ahead of conventional timekeeping,” was selected as the official timekeeper. Epson, a Seiko Group company and then named Suwa Seikosha, played a part in the Games. The company had developed a crystal chronometer based on quartz watch technology from the 59A project. In addition, the company developed, and for a time marketed, a printing timer. This quartz oscillator-type digital stop clock offered electronic timekeeping, a digital display, and a printing option.

These innovations paved the road to unprecedented speed and accuracy, and the company’s timekeeping business flourished. The words, “for the first time no one complained about the timekeeping,” spoke volumes.

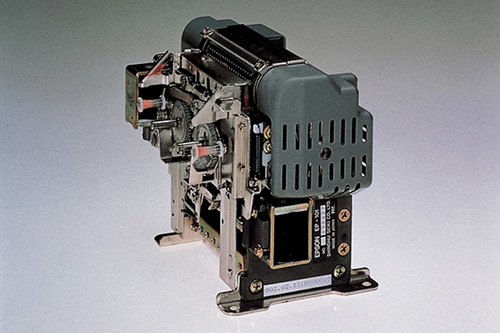

This success was followed by the world’s-first compact, lightweight digital printer, the EP-101 (1968). The following year, the world’s first quartz watch, the Seiko Quartz Astron 35SQ, was launched.

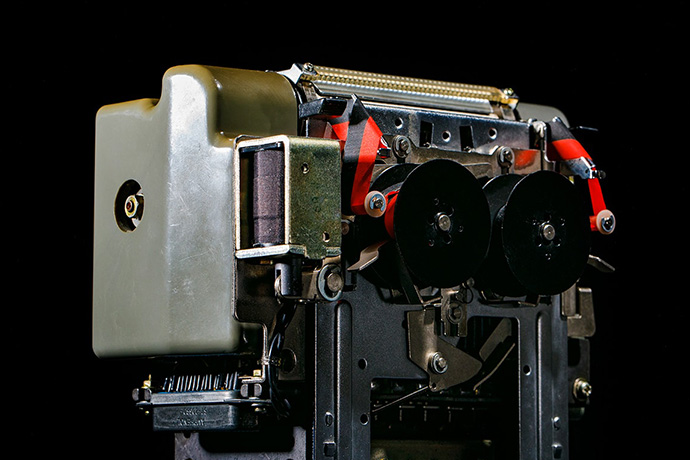

Development of the EP-101

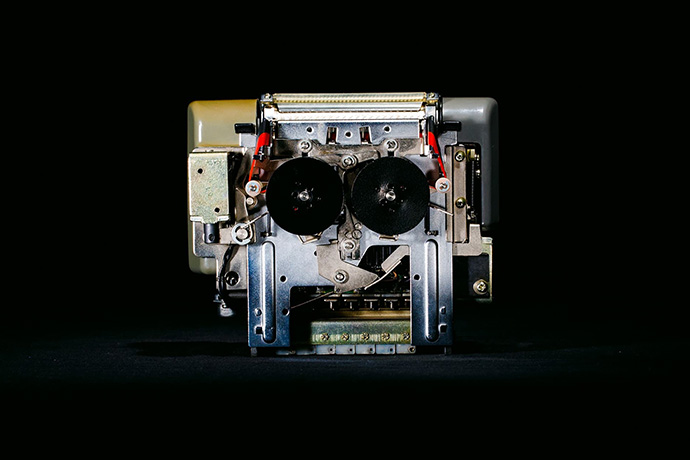

In the years following the 1964 sports event, the company transitioned into a comprehensive manufacturer that handled its own marketing, sales, and service. In the latter 1960s, when electronic desktop calculators first emerged, the company focused on small printers that had potential applications in calculators. The results was the commercialization of the EP-101, in 1968.

The EP-101 marked a new era in digital printing. The printer was lightweight and small enough to fit in the palm of a hand. Moreover, it used 1/20th the power of conventional printers. Epson developed the printer in the spirit of if it doesn’t exist, we should make it. This concept in the information equipment field became an opportunity to exercise the company’s compact, efficient, and precision technologies cultivated through watch manufacturing. The EP-101 exceeded expectations, selling a cumulative total of 1.44 million units.

The development of the EP-101, a printing timer that was used to quickly and accurately time international sporting events, spawned what is now the company’s core business: printing solutions.

Never satisfied with the status quo. The highest standards of craftsmanship.

The challenge to develop a quartz wristwatch continued. The goal was to reduce a quartz clock to the size of a wristwatch, saving space and power. To achieve this goal, the company had to overcome many hurdles. Specifically, it had to produce a crystal oscillator, electronic circuits, and motor in sizes that didn’t exist. Ultimately, Epson made them in-house, as procuring them from outside sources would bring a new set of problems.

In 1969, the company introduced the world’s first quartz wristwatch, the Seiko Quartz Astron. This ushered in a new era of timekeeping many other achievements and accolades would follow, including a prestigious IEEE Milestone Award (2004) and Heritage of Future Technology (2018 and 2019), acknowledging the company’s contributions to technological development for the world. Among the achievements was the first LCD digital quartz watch with a six-digit display, launched in 1978.

From the printing timer and the EP-101 to the commercialisation of the quartz watch, all products represent innovation. If something doesn’t exist, we make it ourselves. This spirit of creativity and challenge has never wavered and remains today.

Chapter 5 - Epson strives to solve societal issues around the world.

The spirit of creativity and challenge lives on. Always, and forever, with you.

The first digital printer, the EP-101, brought new value to the world.

Our name, Epson, reflects our desire to create printers that follow in the footsteps of the EP-101. Children of the EP or EP SONs. Since then, we have delivered many of these children into the world, not only in Japan.

We planted the roots for a culture of home photo printing and created a culture of large-screen office presentations. However, beyond every summit lies more. Aspirations aren’t things to be decided by others. They are ours to decide.

Regardless of the era, we must forge forward. At home, in the office, in commerce and industry, everywhere, we must take the challenge to close resource loops and add new value to what has been used. We use what we need, when we need it, and only the amount needed.

We emerged from Suwa, Nagano. As our predecessors opened the way to a new world, we too will pioneer a path to the future, achieving sustainability and enriching communities.

Solutions on a global scale to reach as many people as possible.

Epson’s vision is to use new technologies to solve the world’s problems and make dreams come true.

In 1975, we established the Epson brand with an aspiration to develop new printers and other information equipment and to enter the global market. The brand name reflects our desire to continue to create many products and services, or the “sons” of the EP in a variety of fields, just as the EP-101 digital printer, which was a huge hit, provided new value to our customers.

This same year, we established our first overseas sales office, Epson America, Inc. Today, Epson has a worldwide sales network and delivers products to people all around the globe.

Printing innovation began with the EP-101 led to the Epson Stylus Color, the world’s first color inkjet printer. Delivering 720 dpi resolution, this product established the home color and photo printing culture. In 1989, we launched the VPJ-700 LCD projector, and since then, we’ve created and fostered a large-screen presentation culture that uses projectors. Today, Epson’s realm of expertise extends beyond printing and projection. Our innovations have revolutionized manufacturing. Our sensing technology enhances lives. Our research is spawning solutions for environmental issues. Epson delivers new value to the world.

Our Innovations

Printing innovations

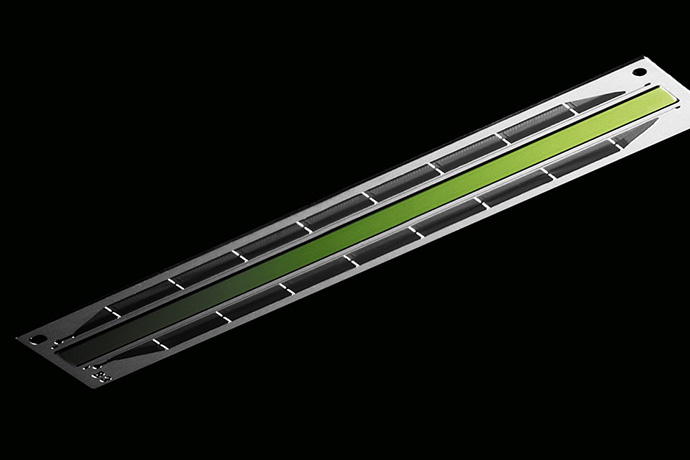

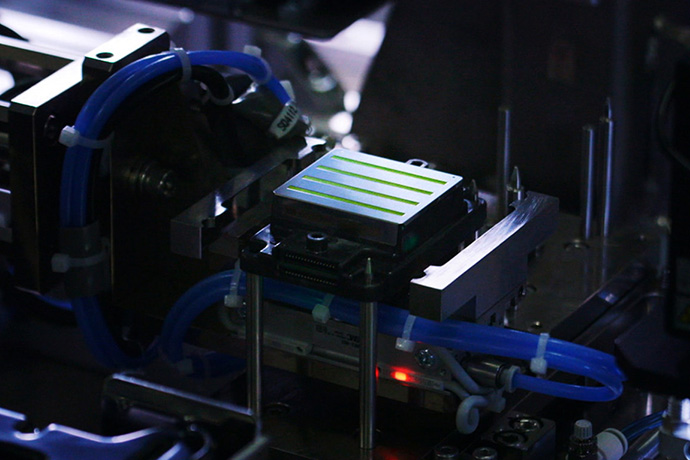

Epson began developing one of its core businesses, inkjet printers, in 1978, using piezo technology for printer heads — the key technology in Epson’s inkjet printers. The method doesn’t use heat to eject ink, so the printheads are more durable and maintain superior performance for far longer. Advancements in piezo technology led to PrecisionCore printhead technology, which delivers stunning image quality at substantially higher speeds while consuming little power. This core technology enables a wide range of applications in home, office and industrial and commercial settings.

Our technology - Piezo method launches a revolution in printing innovation - the continuous evolution in technology and societal contribution.

Epson’s proprietary Micro Piezo inkjet technology

Epson’s Micro Piezo printheads lie at the heart of all Epson inkjet printers. This unique technology has been the driving force behind the growth of Epson’s printing solutions business.

Inkjet printing is accomplished by ejecting ultra-fine ink droplets directly onto media such as paper. Originally, the most common inkjet printing technology was thermal inkjet printing, which uses heat to eject ink droplets. Epson, however, opted to focus on piezoelectric technology and has continued to innovate the technology ever since.

Piezoelectric printheads eject ink mechanically rather than by heating. Piezoelectric elements that change shape when voltage is applied provide the mechanical force. Since they do not heat the ink, piezoelectric systems are compatible with a far wider variety of inks and far more durable than thermal systems. Piezoelectric printheads precisely and accurately control the deposition of ink droplets to deliver both outstanding image quality and high speeds.

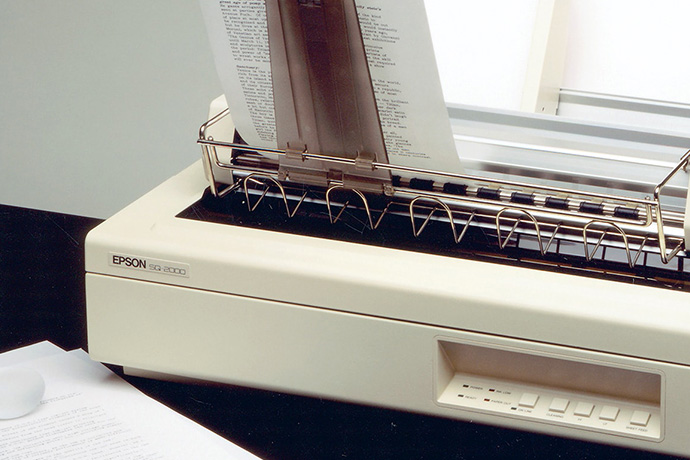

Epson’s first inkjet printer, the IP-130K (known as the SQ-2000 outside of Japan), launched in 1984. It was a piezoelectric system and was well received for business use. Epson’s efforts to advance the piezoelectric printheads culminated in the development of proprietary Micro Piezo technology.

The path to their development was extremely steep and difficult, but Epson’s R&D team overcame the many challenges and obstacles along the way.

The first clear path to advent of Micro Piezo technology

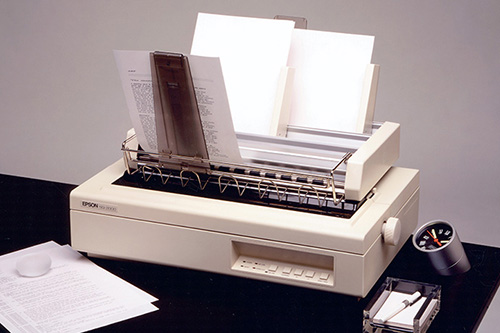

Around 1980, Epson’s printing business was growing rapidly. Growth was driven by the TP-80, the company’s first dot matrix printer (1979), and the MX-80, a printer for personal computers (1980).

However, the market landscape changed suddenly when a competitor released a laser printer in 1984. Dot-matrix printers could not match the quality and speed of these laser printers. Epson immediately recognised the threat to its business and reacted with a sense of urgency.

Within a few years, Epson would come across a chance clue that would enable it to overcome the threat. The clue involved piezoelectric technology. In 1989, a European company proposed using piezo elements as actuators to drive the printheads in dot matrix printers. That is when a member of Epson’s development team who was present at the meeting came up with the idea of applying piezoelectric elements to piezoelectric printers instead of dot matrix printers. This was the first major step toward the development of Epson’s Micro Piezo technology.

Up to that point, Epson had been struggling with the high drive voltage and small changes in the shape of piezoelectric elements. But now Epson realised that these issues could be overcome by using multi-layered piezoelectric elements, which undergo greater changes in shape at lower voltages. With this discovery, Epson was able to establish technology that could compete against laser and thermal inkjet printers.

Ever-evolving Micro Piezo printheads and their contribution to society

Major technical challenges had to be overcome to develop Micro Piezo technology. First, the piezoelectric elements are made of a ceramic. The conventional way to produce the elements was to bake the ceramic like a brick, slice it thinly, and then polish it to the desired thickness. However, ceramic becomes very brittle when baked and the piezoelectric elements would crack or break when reduced below a certain thickness.

To overcome this technical issue, the development team came up with the idea of creating piezoelectric elements by stacking many thin layers of about 20 micrometers like a ceramic capacitor and dicing them into appropriate shapes to make an actuator. Thus, a thin-form piezo was achieved by creating the multi-layered structure before baking and stacking the piezoelectric elements in strips. This method was a game-changer in piezoelectric technology.

This is how Epson, through a length process of trial and error, successfully developed the Micro Piezo printheads which paved the way to thinner piezoelectric elements and smaller printheads.

Micro Piezo printhead development started in 1990, and mass production was achieved by the end of 1992. In 1993, the Epson Stylus 800 monochrome inkjet printer became the first product equipped with as Micro Piezo printhead. Micro Piezo technology continued to evolve. The next generation heads were dubbed ML Chips (multi-layer ceramic with hyper integrated piezo segments). Their piezoelectric elements were less susceptible to damage, which made the heads easier to produce in quantity. The were followed by TFP (thin film piezo) printheads, which had the thinnest piezoelectric elements possible, and finally by Precision Core printheads, which held the key to higher speed and image quality. Micro Piezo printheads not only deliver superb performance, precision, speed, and image quality, but they also operate on low power, making them better for the environment. These features have enabled Micro Piezo printheads to quickly expand into the commercial, industrial, and office printing segments.

Epson’s Micro Piezo printheads have the potential to evolve even further and meet an even wider range of needs. Printheads that are denser and more compact will enable higher image quality at a lower cost. Those with more nozzles will be able to print at even faster speeds. Advances like these will allow Epson to provide more reliable commercial and industrial inkjet printers.

Epson will continue to ceaselessly innovate and evolve Micro Piezo technology into the future.

Projection innovations

By developing microdisplay technology, we gave the world an innovation that is indispensable for recreating true and vivid color images. However, this arm of our business ran into trouble, and at one point, was in jeopardy of failing. Market research helped us navigate these difficult waters. We visited customers around the world looking for problems in their fields and found new ways to solve them with innovation.

We developed projectors that deliver large images offering both high quality and high definition that are easy to see from any angle. Today, our projectors are used in offices, homes, education, and even digital art through projection mapping, providing excitement and surprises to many people.

Our technology Breakthrough after relentless market research and steady efforts: Looking back at the history of visual innovation.

Connecting the world with microdisplay technology

Microdisplay technology lies at the heart of Seiko Epson’s LCD projectors and other visual communications products. It combines Epson’s proprietary HTPS (high-temperature polysilicon TFT liquid crystal) panel technology with various optical and design technologies.

Before LCD projectors, projectors were large and heavy, not portable, and required room darkening due to their low brightness. However, Epson’s 3LCD projectors, the world’s first projectors to use three HTPS panels, are characterised by their brightness and ease on the eyes. Not only has it contributed to the culture of large-screen presentations, but it has also been used in educational settings and home theaters. Thus, we have maintained the top share in the 500+ lumen projector market during the 20 years from 2001 to 2021.

Epson’s microdisplay technology has its origins in the Seiko Quartz LC V.F.A. 06LC, the world’s first digital watch with a six-digit LCD display, introduced in 1973. The product was highly regarded for its display which offeres low power consumption and high visibility. Epson went on to launch a liquid crystal business for areas other than wristwatches. This eventually evolved into the current projector business.

However, not all was smooth sailing at first in the projector business.

Development of the VPJ-700, a compact full-color LCD video projector

In 1988, Seiko Epson became the first in the world to adopt LCD technology in a projector, and in 1989 launched the VPJ-700, a compact full-color LCD video projector.

However, selling the world’s first projector was not easy. The engineering team was expanded to more than 20 members to launch the improved VPJ-2000, but sales did not increase, making the situation worse. At the time, video cameras and other products were becoming increasingly popular, but the need for LCD projectors as a device for projecting images in daily life and in business was limited.

With business continuity in jeopardy, the management decided to downsize and rebuild the business. The first action they took was to research the market by visiting customers around the world.

The last chance: discovering opportunities

Five engineers and two sales representatives were chosen to reinvent the LCD projector business. Considering that the original team had around 20 people, the team was trimmed considerably.

The members started visiting various client companies around the world. With the repetition of these steady efforts, they successfully discovered a specific need in the market.

It was in the US where personal computers were in wide use and business presentations were commonplace, to deliver presentations on a large screen connected to the PC.

Seeing that the spread of personal computers had the potential to expand the projector market, the team identified key factors were not only brightness and high resolution to enable projection in brightly lit rooms, but also small size and light weight for portability, and finally, direct connection to a PC. With a goal to double the brightness while halving the size and cost, they went on to review the product design and team structure.

While the development team worked to increase product competitiveness and reduce cost, the production team and sales team continued to expand their operations. They repeatedly visited distributors and carried the prototype around the world. Once distributors could see the actual difference in brightness and resolution, they knew they could sell Epson’s products.

Establishing a market: in further pursuit of visual innovation

Having achieved small size and high resolution, the ELP-3000, the world’s first data projector was released in 1994. At the time, Windows 95 was in wide use, creating more opportunities for people to make business presentations. This became one of the drivers of the explosive sales of the ELP-3000, which was designed to project data from a personal computer.

In 1995, Epson reached top position in the domestic projector market. The steady work and the contracts that the team secured on their own feet bore fruit. The company continued to introduce new products and establish a culture of using projectors for large-screen presentations in the office.

Meanwhile, in 2002, Epson entered the home projector market in full-scale with the ELP-TW100, adding color to people’s lives. Also making progress in the field of education, the company is now helping to build an environment where every student can receive equal education.

Regarding technology, microdisplay technology has been applied to products such as smart glasses, while laser light source technology has been applied to projectors. In addition to bright and vivid image expression, product longevity and ease of installation has been realized. Through these achievements, the use of projection mapping for digital art and digital signage in commercial facilities has expanded, and through its images, projectors have now become a source of excitement and surprise for many people.

Epson’s innovations in visual communications continue to support learning, working, and living by connecting core technology-driven products with people, products, information, and services, ultimately improving the quality of life and advancing the frontiers of industry.

Innovation to reduce environmental impact

As a leading printing company, we looked for solutions to paper waste after printing.

The fruit of our pursuit was the “PaperLab”. PaperLab is the world’s first1 dry process office papermaking system that can produce new paper from used paper using virtually no water2. We exhibited the system at Eco-Products 2015, the International Exhibition on Environment and Energy, creating a big hit with the public. The PaperLab is equipped with “Dry Fiber Technology,” which turns paper into fibers by impact force without the use of water. It helps to build a small cycle of paper recycling, enabling recycling and use of paper in places like the office, for example. Our concept of this cycle is not “recycling. It’s “upcycling”, a way of adding new value. Currently, we are pursuing the application and evolution of “Dry Fiber Technology” to materials other than paper, together with a wide range of co-creation partners. We will continue our efforts to deliver new value to the world toward achieving sustainability and enriching communities.

Our technology: Innovations that envision the future: Dry Fiber Technology

Focusing on the issues of printed paper: Two perspectives that lead to breakthrough in development

It was 2010 when then-president and representative director Minoru Usui posed a question to the technical development team. He told them that there must be something a leading printing company like us can do about it.

This prompted Kazuhiro Ichikawa, then leader of the technology development team, to start visiting government offices, corporate offices, and financial institutions to observe how printed paper was being used and disposed of.

He found that most of the printed matter carried confidential information and that its disposal was outsourced to an outside contractor, incurring costs. Customers were not satisfied with the situation.

At the same time, he visited paper mills and industrial testing centres to conduct research from various angles, from paper manufacturing to recycling. He learned that large amounts of water are necessary to recycle paper while avoiding the risk of water pollution, and that wastewater treatment is expensive. Looking outside of Japan, he learned that not all regions have abundant water resources, adding to more challenges in paper recycling.

We discovered an opportunity for development that focused on closing the resource loop and protecting confidential information.

A new challenge: Recycling paper in a virtually water-free process

Once the challenge was identified, the technology development team focused on how to build a recycling method that uses virtually no water and yields high-quality paper.

However, it was a challenging goal to achieve. When they shred the paper too finely, the paper fibers were chopped, and high-quality paper could not be made. Trial and error continued. Even after more than 100 different experiments such as scraping paper with mortars and grinding them with mixers, no solution could be found.

The breakthrough came when Ichikawa tore off a piece of washi, traditional Japanese paper, with his fingers, and noticed that the fibers along the torn edges were loose and could be teased out. He thought that maybe it would be better to separate these fibers by loosening and untangling them instead of through a cutting, rubbing, or crushing process.

This idea led to the development of Epson’s Dry Fiber Technology, which features a combination of processes in which used paper is defibrated (thus securely destroying all the printed information on a page) and new paper is produced from those fibers. To verify whether this technology would really be accepted by the market, Epson demonstrated PaperLab, the world’s first1 dry process office papermaking system that can produce new paper from used paper using virtually no water2 at Eco-Products 2015, the International Exhibition on Environment and Energy. The PaperLab became a big hit with the public.

Opening up possibilities for upcycling with Dry Fiber Technology

“Dry Fiber Technology” not only defibrates, binds, and molds paper as needed for a given application, it also enables processing and treatment that were previously impossible, reducing waste and taking advantage of new material properties.

The PaperLab led to the creation of more than recycled paper; it also created new value. “Dry Fiber Technology” provides an upcycling solution rather than a recycling solution. It is precisely the type of social contribution Epson had always wanted to make.

Until now, recycling has often been viewed as something that returns something of lesser value, as not many recycling technologies were able to generate new value. Epson, however, hopes to expand the culture of upcycling as a way to create new value.

By using “Dry Fiber Technology” to give value to what used to be disposed of as waste, we will reduce the environmental impact of manufacturing.

What can we do for the future? Achieving sustainability and enriching communities

Epson is currently working with like-minded partners to develop “Dry Fiber Technology” upcycling applications for a variety of materials in addition to paper. We are also working on ways to use “Dry Fiber Technology” to produce new materials to replace petroleum-based materials such as plastics. Epson will continue to develop technologies, products, and solutions that are sustainable and that enrich communities.

Note1: Among all dry process office papermaking systems. Source: Epson’s research conducted in November 2016

Note2: A small amount of water is used to maintain humidity inside the system.

More about Epson

EME (META-CWA) Executive Team

Innovation

About Epson

Support

Visit our support page to find drivers, software, manuals, FAQs and how to contact us.

Register your product

Product registration is quick and easy.